five more voices

~ five writers, each issue ~

generations of West Virginia creative writing

You're invited

to feel proud!

For an

intro,

click the "About"

tab

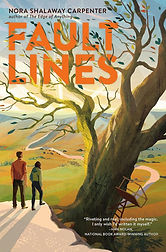

Nora Shalaway Carpenter

NPR Best Books of the Year

Kirkus Review Best Books of the Year

Green Earth Book Award, The Whippoorwill Award

Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection

Nautilus Book Award: Gold Medal

Bank Street Best Books of the Year

She's a hot ticket in the world of young-adult writers

Northern panhandle native Nora Shalaway Carpenter has had big success as a writer for young adults. We asked if she'd hand out advice to her West Virginia compadres. She mixed stories from her life in with some excellent tips.

Tip #1: Use your own experience

Read Nora's books if you want to get to know her. She uses her life experience when she creates characters and plots.

“Even if your actual experience isn’t the experience of your character,

you can use your own emotional experience. It helps you know what your character is going through,” she says. “If you’ve been disappointed, for instance, you can draw from that to show how your character feels when she’s disappointed.”

In Nora's first young adult novel, The Edge of Anything, Sage, an ambitious high school volleyball player, dreams of a sports scholarship. Her hopes are dashed by a medical problem. N0ra had a very similar experience.

Len, a high schooler, goes through a traumatic experience that leads to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Nora has experienced OCD. In the book, Len and Sage form an unlikely friendship when their

circumstances bring them together.

Nora is also a bit like both Dex and Viv in Fault Lines, her second young adult novel. Fault Lines explores fracking in West Virginia from a teenage viewpoint. Dex’s family depends on his mom’s job working on a pipeline for a gas fracking company. He’s attracted to the headstrong Viv, who hates what fracking is doing to her homeland.

Like Viv, Nora once drove the roads near her family’s Marshall County homeplace, grieving the way gas well drilling and pipelines were

ravaging the roads and land. “It just didn’t look like home anymore,” she remembers. “They’d cleared out this huge track of forest, and there was this massive pipeline. It was making me ill.” She imitates the shrill, discordant screech of a fracking drill that echoed throughout the hills. “Rrrrrrrrrrrrrraaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhhh.”

After the land was fracked, Nora, didn’t go home from college as often. Her parents “held out for a very long time and eventually came to a deal for a right-of-way.” Then they moved to Asheville, North Carolina, to be close to Nora, her lawyer husband Josh and their three children.

Tip #2: Find role models who let you know that

“you can do this.”

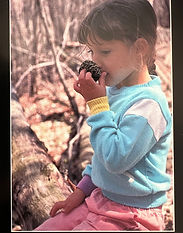

When she was small, Nora didn’t have to look far for a writer role model. Her father, the well-known outdoors columnist Scott Shalaway, had

walked away from an academic career to create a back-to-the-earth lifestyle for his family while he built a writing career as a freelance outdoors columnist.

“He was always dragging us out into new experiences, taking us canoeing

and stuff, and he’d say, ‘You can use this experience in your writing one day!’”

Her parents renovated an old farmhouse on 95 acres of land near Cameron, Marshall County. Their early years were lean. “We were really poor. I’m very much from Appalachian culture. My dad wrote freelance stories and he’d get a check for $15, and we’d go get bread and milk.”

At the same time, she knew she was different. “Not many kids I grew up with had a parent with a Ph.D.” Her mom, Linda, taught English at a

local school and was “a little granola,” she says. Her family recycled and celebrated Earth Day before those were popular things to do.

West Virginia Poet Laureate Marc Harshman lived nearby. “I would always

think, ‘Oh, I can grow up and write books like Marc!’” She started creating stories as soon as she could write words. "There were always tons of books in the house. I went from The Giver to Charles Dickens, and other books that were considered young adult when I was growing up in the ‘90s, like A Wrinkle in Time and the Harry Potter books.”

From third through 11th grades, every year she won first place in West Virginia’s Young Writers competition. Her story, “My Verse" took the top statewide prize in 2000 for the 11th and 12th grade division.

Nora graduated from Marshall and got an MFA at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Now 42, she has published two young adult novels and edited four short-story collections that also include other writers. Her books have won many national awards.

Her calendar is packed. She often travels to conferences and schools to talk about her work and things she cares about, while keeping an eye on her own projects and taking care of her three kids, sons Garek, 13 and Zander, 10, and daughter Lyra, 7. “They’re proud of what I do, and I’m never away long,”

In early May 2025, she delivered

the keynote address at Young

Writers Day at the University of

Charleston, the same contest she

won so often as a child. “It was so

wonderful,” she remembers.

“These students came up and

talked to me and I could see that

they had the same drive in their

eyes. It was so awesome.

“Some of these kids, I’m going to

be reading their books soon.”

Nora makes dozens of talks every year, but this one was special: the 2025 keynote address at Young Writers' Day in Charleston.

Tip #4: A plot outline (a story map) can help.

She learned a lot by working with publishers. Nora's first novel never got published, but an editor loved her writing and asked to see 50 pages, plus an outline of a different book.

Nora had two books in progress, one about Sage, a high school athlete who plans to go to college on a sports scholarship, then learns she has a heart condition that blocks her from doing intense exercise for the rest of her life. The second story was about Len, a teen photographer who is shunned at school because her obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The editor asked her to submit an outline. “It changed the way I write novels and stories,” Nora says. “Before, I would write by the seat of my pants. I’d sort of know where I was going, but I wouldn't have any real guide or plan.”

Nora suddenly saw that the Len and Sage stories could become one story. She placed Len in the gymnasium stands when Sage collapses at a game. Neither story alone made sense, but combining them did. The outline of their combined stories, plus 50 pages, sold the book.

Her advice: Many short pieces don’t need an outline. But for complex pieces, first spend a few weeks figuring out what will happen in the book. “It’s so much easier that way for me,” she says. “I’m a mom of three busy kids. I don’t have time to figure out what needs to happen in the story every day. An outline provides a map. I look at it and know, okay, today I need to write a scene where X, Y and Z happens. It was really revolutionary to me.”

Tip #5: Show the motivations of all your characters, even those you don’t agree with.

Nora's second novel, Fault Lines, starts with Viv up in her family’s tree stand, a refuge that comforted the lonely girl, who has lost both her mom and her aunt. Suddenly, the stand begins to give way. Viv jumps down just in time, before it collapses. She learns that the gas company’s fracking caused a sinkhole that destroyed her beloved hangout.

Then, she meets Dex, who just moved to her area. She

is attracted to him until she learns that his mom

works for the fracking company. Still, they spend

time together.

Viv feels a magical connection to the land. Dex’s mom needs her paycheck. “Readers need to understand why characters do what they do,” Nora says.

Viv and Dex argue about chopping down trees.“I don’t think we should chop down trees for fun, but we have to have energy,” Dex says.

“Right, but there are lots of earth-friendly ways to get energy. Solar. Wind. Ocean—” Viv answers.

“Are you saying we should never cut down trees?” Dex interrupts. “Because that’s ridiculous. Trees are renewable. And if we didn’t have fracking, where would we get the 17,000 barrels of oil that this country uses every day?’”

These conversations help Fault Lines give readers a rounded view of a complex topic. After Viv pooh-poohs his argument, Dex replies, “Do you have solar panels on your roof? Or a wind turbine hidden somewhere? Because I sure didn’t see any on your property."

Community! All of these writers contributed a story to the anthology, Onward: 16 Climate Fiction Short Stories. Nora is the editor, so she got to know them all!

Tip #6: Create a writer community for yourself.

In 2019, Nora pulled together an award-winning short story collection called Rural Voices, including stories from 14 other authors who “challenge assumptions about small-town America." She was making money for herself and others, but it was more than that.

She also got to know all those writers, expanding her own writers’ community. “To survive as a creative, you need a community,” she says. “When I was talking to other authors like me who were rural, who had grown up rural, we all had these really strong memories from our young adult years of being stereotyped because of where we are from,” she says.

Rural Voices won multiple awards. Since then, Nora has edited three more collections:

-

Ab(solutely) Normal: Short Stories That Smash Mental Health Stereotypes. This one includes classroom resources and activities.

-

Spinning Toward the Sun: Essays on Writing, Resilience and the Creative Life: 30 authors donate 100% of proceeds to flood recovery

-

Onward: 16 Climate Fiction Stories to Inspire Hope (Just published!)

Both Rural Voices and Ab(solutely) Normal were “universal reads” at at least two colleges. Every student reads the book and does assignments from it. Nora visited a writing camp where students created their own Rural Voices collection. “It made me feel great to see them writing their own stories, using my work as a model,” she said.

Tip # 7: Fight stereotypes

Nora is a sworn enemy of Appalachian stereotypes. “I’ve internalized, rejected, and combatted those stereotypes my entire life,” she told the Vermont College of Fine Arts newsletter in 2023. “I’ve code switched and hidden my rural roots in certain situations to be afforded more respect, and I’ve been demeaned for nothing more than where I call home. I am accustomed to being overlooked, undervalued, and having to fight for any space at numerous tables. But rural tenacity is a real thing.

"I know my rural truth, and I know it’s not reflected in most popular media. I will forever work to change that.”

She recalls a painful incident from her own life. At a Washington, D.C. party, somebody mentioned that both she and her husband were from West Virginia. “And the first thing someone said was, ‘Oh, is he your cousin?’ And the whole room cracked up,” including her friend.

Nora responded angrily. “They would defend just about any group of people from discriminatory language. And then they do the same kind of behavior to rural people.”

Anger at that kind of demeaning attitude drives her. She dreams of populating bookstore shelves with realistic stories about West Virginians and Appalachians. “I’m passionate about rural places and breaking stereotypes,” she says.

“I think the more we can humanize people, the better life will be for everyone. That’s a lot of what I try to do with my writing.”

Nora is a popular guest on podcasts and radio

shows.

The books she has written and edited reflect her passions: teenage mental health, climate change, creativity, and stereotypes of rural people. Here

are a couple of great podcasts featuring her.

* Nerdy Book Club: Why Story Matters

* Worlds, Images and Words: Connection to Appalachia

Sample from Fault Lines

Background: Viv, 17, is angry because fracking is tearing up the woods and roads of her rural And her dad is talking with the fracking company about giving them the rights to put a road trough their land.

Her dad says they need the money for Viv's college. Viv says, no way! Then she comes home from school to find her dad drinking tea with a man from the fracking company.

"The next day, Viv returned home from school to find a man sitting and laughing with Dad on the front porch rockers, despite it technically being winter. Each of them held Mason jars filled with the sweet tea she'd brewed that morning.

"Ah, Vivi," Dad said, "you remember Reggie Thompson? You used to help me load firewood off his land years ago."

"Hello there," the man said, his smile as wide as a car salesman's. "Last time I saw you, you were only yea high," his hand raised to his chest.

"Um, hi," Viv said, giving her father a questioning glance. Then her eyes zeroed in on the company emblem on Mr. Thompson's shirt: SEI Energy Natural Gas. She sucked in her breath.

"Reggie here saw the article in the paper," Dad said. "He realized it was talking about our property."Viv was sure she didn't imagine the tiny hitch in Dad's voice when he added, "Our tree that collapsed."

Mr. Thompson pursed his lips sympathetically. "I am sorry about what happened, Vivian."

"Viv," she corrected.

"Of course, I knew nothing about it," Dad added, staring at her, and she knew from his tone that he had a good many things to say about that, but not in front of Reggie Thompson.

Viv held up her hand. "You said something about a newspaper article?"

Mr. Thompson passed over the County Times. "Page four."

Viv flipped to the page. There, just above the fold, were several of the pictures she'd sent Ms. Giang. A bolded headline read: Local Tree Sucked Underground. Fracking to Blame?

She skimmed the article long enough to see that there was no mention of her name or her father's ...

"I didn't talk to any newspaper," she said. Then because she resented having to explan herself in front of a man who worked for the very company that was most likely responsible for destroying

her most beloved space in the world, she gave Mr. Thompson a cold stare. "How did you know where it was, anyway?"

"Ah, Google Maps is a wonderful thing." Mr. Thompson's voice was honey, smooth, his smile seemingly gneuine. "As I told your dad, SEI Energy doesn't take responsibility for this unfortunate accident, seeing as how it has no lines on your property, but we also take our role as good neighbors very serioiusly."

"They gave us a check," Dad said.

"We understand your hunting stand was destroyed," Mr. Thompson said. "I know it was special to your family. We wanted to help you get the supplies to rebuild."

She stared at Mr. Thompson, willing herself to feel something, anything, about this man smiling before her...

Dad cleared his throat and Viv realized how she must look. She fought to compose herself.

"It's very generous of you all, Reggie," Dad said. "Thank you."

"Generous?" Viv scoffed. "Sounds to me like you're trying to guy us off."

"Viv." Dad's tone was a warning.

"Really?" she snapped. "You don't think it's suspicious? If they had nothing to do with it, why give us money?"

Mr. Thompson slowly swirled the tea in his jar. "Just trying to be neighborly."

"Neighborly, my ass," Viv muttered.

Sample from

The Edge of Anything

Sage, a popular, athletic high school girl, passed out while playing volleyball. Now she is rushing down the hall with her friend Kayla. They literally crash into Len, one of the school outcasts. Len suffers from obsessive-compulsive disorder,

They turned a corner just as another girl rounded it, and Sage collided full force with her.

"Oh!" The girl's fistful of pens scattered to the floor.

"I'm so sorry," Sage said. "I didn't see you."

The girl froze, her gloved hands clenched stiffly by her sides. She watched two of the pens roll all the way to the opposite wall.

Sage dropped down to gather them. There must have been ten at least, maybe more. Brand new-looking too. Sage appreciated the importance of being prepared - one of the gazillion things volleyball had taught her - but ten pens seemed excessive.

"Don't worry about it," the girl said, her voice slipping out like an accident.

"No, it was my fault." Sage stood up, both hands full of pens.

"You're that volleyball player." Gloved girl tilted her head.

"Oh. Uh, yeah. I'm Sage."

"Are you okay?"

It took Sage a moment to realize the girl must have seen her pass out. Or heard about it. "Yeah, I'm fine. Here are your pens." She nodded at the floor. "The last one's by your shoe."

Gloved girl stared at Sage's outstretched hand, expressionless. Behind Sage, Kayla gave an awkward couch.

"Right," said Sage. She hesitated a moment, then collected the final pen.

The girl inched backward. "You can keep them."

Sage frowned, suddenly uncomfortable. "Um, they're yours."

For just a moment, she held the girl's eyes. Gloved girl dropped her gaze, but not before Sage saw the panic that filled it. Sage glanced at Kayla, who was staring at them the way people watch a car crash.

"Please take these," Sage said. The warning bell rang above them. Slowly, the girl nodded and took the pens.

"Coming through!" A herd of sophomores...barrled around them. Gloved girl backed up, a move that seemed as instinctual as Sage's volleyball sprawl. Mumbling a quick thank you, she hurried back the way she'd come.

Sage's eyes followed her. "That was ... weird.."

"You think?" Kayla said. "But it's Len Madder, so ..."

"Here last name's Madder?"

"I know." Kayla made a face. "An unfortunate coincidence since she's legit crazy."

Sage couldn't remember ever having seen the girl before. That wasn't out of the quesiton, considering the size of the schoo, but it was more than that. Een now, she had trouble remembering what the girl had looked like: babby sweatshirt...gray maybe? And was her hair brown? Or more blond? Sage frowned. It was like the girl - Len - had been a part of the background until the whole pen incident forced her into visibility. A person had to really try to be that unnoticeable, didn't she?

They'd reached their lockers. Sage turned back to Kayla. "So you know her?"

"She's in my study hall. She's a junior, though." Kayla spun her lock until it clocked. "She seemed normal enough at first, but trust me, she's not."

"Why?"

Kaya shrugged. "It's hard to expain. She just does weird things, you know? Like" -she flicked her hands - "whatever that was."

Mary Wade Burnside researched and interviewed Nora and wrote the story.

Mary Wade Burnside is a 30-year career newspaper reporter, 13 at the Charleston Gazette in West Virginia. After stints in Nashville as a reporter for B2B magazine Amusement Business and as a magazine editor in West Virginia, she now works as a health department public information officer. Her work has won West Virginia Press Association awards and she was named CNHI Reporter of the Year, Division 2, in 2011. She lives with her husband and their cat in Morgantown. In her spare time, she practices yoga, reads and enjoys films.